Malak Sheth

INTRODUCTION

Wasiyat is a concept in Islamic law that allows a Muslim to dispose of a portion of his property or assets through a written will which cannot be in excess of one-third of such property. The same is ordained under Muslim law so that the dependents or the heirs of the testator are not left destitute or on the streets. Thus, even in extenuating situations wherein the Muslim person was ill-treated throughout his life by family members, he would still be compelled to give them a share out of his property. Two-thirds share of the property that cannot be willed out because of the conditions of limited Wasiyat under Muslim Law shall devolve as per the rules of Islamic inheritance to the heirs of such a person.

The author, through this piece, first argues that such a limitation imposed upon the absolute ownership rights of a person is a quandary that has no constitutional remedy. Secondly, the alternatives for full transfer of property such as Hiba under Muslim Law or registration of Marriage under the Special Marriage Act 1954 are highly restrictive and thus untenable. Lastly, the author makes a case for a fundamental right to choose the applicability of secular laws or personal law for different aspects of one’s life such as marriage, devolution of property and so on.

RIGHT TO PROPERTY: A MISSING CONSTITUTIONAL REMEDY

Every human being has a natural right to property which not only includes protection from arbitrary state action but also includes the right to transfer the property to others (by sale, rental, gift, loan or will). Such a natural right was originally recognized by the Indian Constitution through Article 19(1)(f) which gave the rights to acquire, hold and dispose of property; however, the same was abrogated after the 44th Constitutional Amendment in 1978.

The new constitutional right under Article 300-A is a limited one, as it only protects from the arbitrary taking away of property by the state (that is, without the “authority of law”) and does not recognize any fundamental right to property, in the aforementioned ways. Thus, a Muslim person is left without a constitutional recourse in a situation where he wants to devolve more than one-third of his property through a testamentary disposition.

An alternative that allows for a full transfer of property under Muslim law can be through instruments like hiba or gift. However, gifting the property would mean that the person will have to immediately transfer the rights to his property to the donee, unlike in Wasiyat or Will wherein the rights to the property are transferred after the death of the person. Thus, Wasiyat as a mode of devolution of property, unlike ‘hiba’, allows the person to exert influence over his property when he is alive, and thus, is a more preferred mode of transfer of property than ‘hiba’. Therefore, the alternative of ‘hiba’ can be said to be highly restrictive in situations wherein the donor is not driven by the intentions of goodwill towards the donee but by other extraneous reasons.

The second alternative would be marriage under the Special Marriage Act 1954 or registration of marriage under the same Act as the person would then be governed by the Indian Succession Act 1925 and thus can will away the entire property. However, this would trespass upon his rights under the personal law to marry up to four wives and thus would not find favour amongst the Muslims.

PERSONAL LAW v. SECULAR LAW: A FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT TO CHOOSE

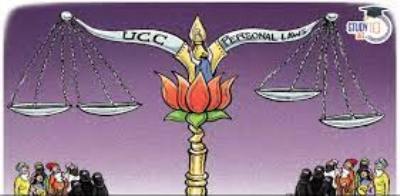

In India, irrespective of personal beliefs, when the state has to decide on the applicability of laws for marriage, inheritance or adoption, it inevitably resorts to the religion of the person (even though the person might be an atheist) for the same. This is because India lacks a framework of secular legislation for these matters that govern its citizens. The author now makes a case for the rights of the citizens to selectively opt out of personal laws in matters of their choice and seek to be governed by secular legislation for those and only those matters.

In case wherein a Muslim person wants to will away more than one-third of his property, he cannot specifically opt out of the Islamic personal law for Wasiyat-related matters, as the only option available is to completely opt out by registration or marriage under Special Marriage Act. Further, if he wants to make such a choice, India lacks a framework of civil code that governs these matters uniformly for all religions.

It is therefore the author’s case that rather than thrusting a Uniform Civil Code that uproots personal law completely from a deeply-religious society, India must come up with a parallel civil code that people can opt to or opt out of for matters of their choice. Such an approach would avoid an insurrection against the Civil Code, and when the time is ripe with a more mature society, it would allow a complete smooth transition from personal laws to a uniform civil code. Further, such an approach also encapsulates within itself the fundamental right to choose of the citizens which the Supreme Court and several High Courts have held to be the “inner aspects” of the right to life. Allowing the citizens to choose between secular law and personal law for matters of their choice would be a recognition of the highest order of the fundamental right to choose what is best for one’s own self, in India.

Furthermore, such a selectivity in deciding on the applicable laws would also be the first step towards solving the problem of Muslim women’s right to property till the community is more forthcoming to changes in their personal law. Currently, even the more egalitarian-minded Muslim adherents who seek to devolve their property equally amongst all their children (inheritance laws amongst Muslims give half of the son’s share of the property to the daughter) cannot do so by will because of the limitations of ‘Wasiyat’ in Islamic law. Thus, all Muslims who are currently unable to distribute property equally amongst their children would be able to do so out of their own volition if the aforementioned remedy is made applicable in India.

Lastly, such a civil code would help in materializing the rights under Article 25 which allow for a fundamental right not to profess any religion as well. The same cannot be said for the contemporary scenario, as even an atheist has to rely on the laws of the religion in which he was born for matters relating to marriage, inheritance and adoption. Such reliance on personal laws, in the absence of a uniform code, even for an atheist, militates against his fundamental rights under Article 25. Thus, such an approach would enable the government to swiftly bring in a politically sensitive legislation while facing minimum resistance and thus fill in the vacuum resulting from the absence of a civil code in India.

CONCLUSION

It can be concluded that a Muslim person being left without any recourse in situations where he wants to devolve more than one-third of his property is against his natural right to property. Further, with Article 19(1)(f) deleted from the text of our Constitution, he cannot even challenge the provisions of personal law which are antithetical to such a natural right by way of a writ petition as no fundamental rights of his are violated, which is patently unjust.

Therefore, the author makes a case for the promulgation of a civil code in India that people can opt to and opt out of for matters of their choice till time is ripe for a complete transition from personal laws.

India has not been able to bring in a Civil Code yet because of it being a politically contentious topic that faces stiff resistance from minorities in India. However, by bringing in a civil code which recognizes the fundamental right to choose when an individual seeks to be governed by it, the issue can be dealt with sensitively. This would not only fill the vacuum present within the laws of the country but also set the ground for a smoother transition since people who would have already benefitted from the secular laws would find it difficult to challenge the same at a later stage.

The author is a second year student at Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, Punjab

Image Credits: StudyIQ

Useful insights. Thanks for sharing

LikeLike

May i ask –‐:

1 . My stepmother has done wasiyatt of parental house of her mother .

2.I me myself + 3 have been born by the elder sister of my stepmother.

MOHD ARIF

Email i d : anarif8951@gmail.com Is it possible that the stepmother could do wasiyatt of her mother , s ( NAANI OF ME MYSELF + 3) IN favour of her own born ladka & ladki ONLY EXCLUDING ME MYSELF + 3 born from the elder sister of stepmother WHILE THE PROPERTY BELONGS TO MY ” NAANI ” .

LikeLike