Samarth Varshney & Upanshu Shetty

INTRODUCTION

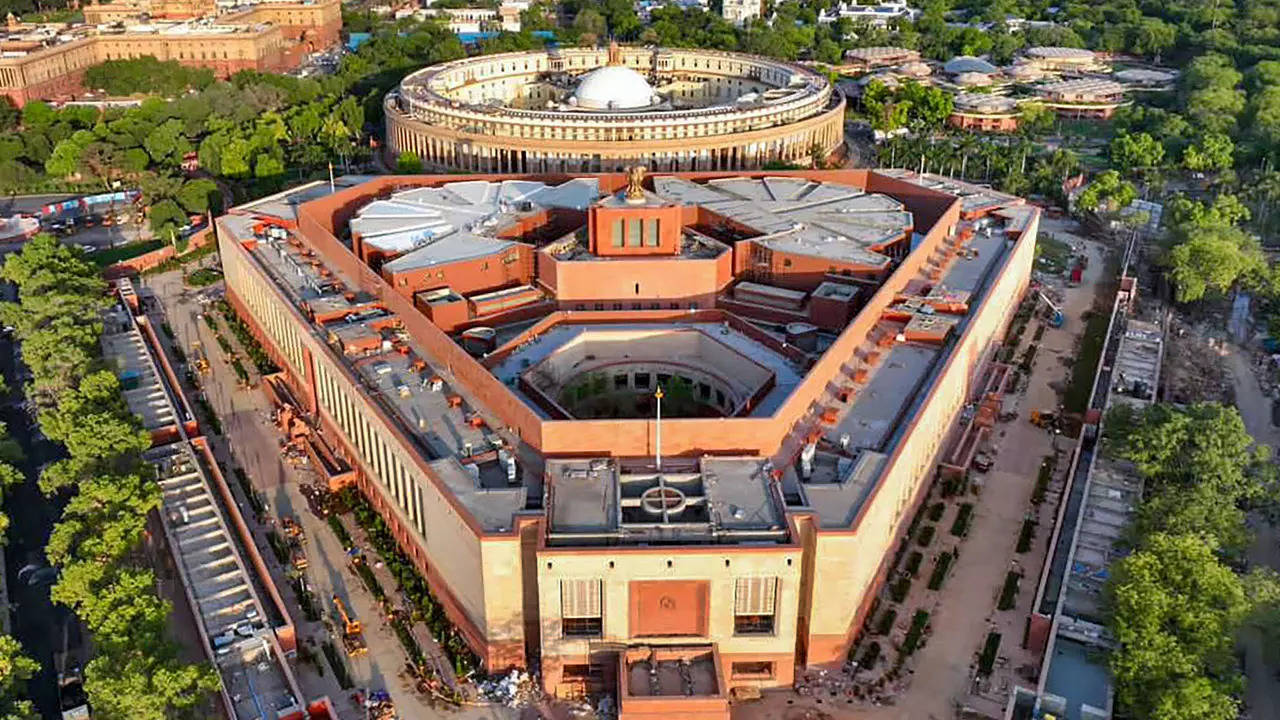

Recently, the parliament has passed the long-awaited Data Protection Bill, despite facing opposition protests, through a voice vote. This legislative development has sparked a significant debate among scholars revolving around the credibility of the decision taken by the governing body.

The process of decision-making within legislative bodies is the cornerstone of democratic governance, where lawmakers deliberate on proposed bills, resolutions, and amendments that shape the laws of a nation. Among the various methods employed to reach consensus, the “voice vote” is one of the most common and expeditious ways to determine the outcome of a legislative matter.

However, the constitutional implications of employing voice votes have been a subject of debate, raising questions about transparency, accountability, and the overall integrity of the democratic process. To attain a heightened level of clarity and lucidity in our discourse, we must embark upon the foundational step of understanding the intricacies inherent in a voice vote.

VOICE-VOTE

A voice vote is a simple yet significant procedure used in legislative bodies to determine the outcome of a proposal without recording individual ballots. Instead of a formal roll call or electronic vote, members verbally express their support or opposition when the presiding officer calls for a vote. Those favouring the decision call out “Ayes”, and those opposed say “Noes”. The side that appears to have the majority based on the volume of voices is declared the winner.

This technique has been used to pass several controversial bills in the parliament, and surprisingly without the majority assent. Notable among them were the three farm bills that sparked an embroiling controversy, which were passed amidst many protests from the opposition. Moreover, the Election Laws (Amendment) Bill (or the Aadhaar Bill), which raised serious questions regarding the infringement of individual privacy, was passed in a similar fashion. The current instance wherein this mechanism was misused was when several bills were passed through voice during protests in the parliament over the Manipur issue, including the Biological Diversity Amendment Bill, 2022, and the Registration of Births and Deaths (Amendment) Bill, 2023.

The practice of voice vote is not restricted to India but is professed in many other democracies around the globe. In the United States, the course gets sanctioned from Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised (11th edition), which imparts a vote by voice for any motion or provision that does not necessitate more than a majority vote for its approval. This article aims to analyse the current procedure of the voice voting mechanisms and the loopholes that threaten the democratic law-making process.

LACK OF ADHERENCE TO THE PRESCRIBED PROCEDURES

Article 100 of the Constitution of India mandates that all the questions in a house shall be decided by the process of voting by a majority. Hence, when the voice-vote mechanism is employed unethically, with decisions being made devoid of proper discussions and bills rushed through amid heated debates and protests, it directly contravenes Article 100. This violation occurs because there is no clear majority consensus on the decision, as mandated by the constitution.

The principle above has been emphasised in Rule 252 of the rules Of Procedure And Conduct Of Business In The Council Of States (hereinafter, Rule 252), the place from where the voice vote draws its legitimacy, wherein it is stipulated that the procedure of a voice vote shall ensue after the culmination of the debate. Rule 252 begins with the phrase ‘On the conclusion of a debate’. This shows the lawmakers’ clarity and intent that this instrument must be used when the discussion has concluded and a decision by a majority is all but apparent.

This rule is Pari Materia to Rule 367 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha and therefore, these provisions apply to both Houses.

Power of the Presiding Officer

In such scenarios, the presiding officers’ discretionary powers are limited. The judgment, whether the ayes soundly outweigh the noes or not, although ideally must be apparent, isn’t so most of the time. Here comes a vast degree of subjectivity and conflict. The remedy against such an undemocratic voice vote, present in subrule (3) or (4) of Rule 252 (and 367 of the Lok Sabha Rules), again lies with the presiding officer.

The process requires questioning the outcome of the voice vote decision, which can subsequently be supplemented by the presiding officer’s choice to conduct a head count for individuals aligning with their respective positions or to call for a division. If the decision is again challenged, there is the provision for division of votes by either going into lobbies or by operating the automatic recorder. Thus, the whole method is aimed towards clocking into an objective decision which the majority of the House agrees to.

But, in practice, the officer exceeds his powers and reject such challenges, thereby violating these, and when questioned, the veil of articles 212 and 122 of the Constitution is sought to avoid judicial intervention. An analysis of this is further done in this blog.

STAKEHOLDERS INVOLVED: THE OPPOSITION’S DILEMMA AND THE JUDICIARY’S POWERS

Rights of Opposition

Parliamentary deliberations not only take a backseat, but opposition members also face arbitrary suspensions, disregarding the Parliament’s internal rules. These suspensions occur through the questionable method of voice votes. In November 2021, twelve members of the Rajya Sabha, representing five opposition parties, were suspended for the entire winter session as they were protesting against the arbitrary procedure of passing a bill in the legislature. The motion to adjourn these members was initiated under Rule 256 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in the Council of States, and ironically, it was approved through a ‘voice vote’.

It is worth noting that the opposition in India faces its structural weaknesses, including the absence of a shadow cabinet and spokespersons with expertise in specific subject matters for scrutinising policies and legislation. Often, the opposition operates primarily to advance its narrow self-interests. Nevertheless, as previously emphasised, it remains crucial to acknowledge the role of the opposition in fostering public dialogue and normalising the practice of ‘dissent’ against the ruling dispensation in society through an official forum like that of the Parliament.

Addressing the Public Interest

Ultimately, any decision affects the public at large, thus making them an important stakeholder. When a bill is passed during protests, the important constitutional schemes of transparency and accountability of the legislature out the window. The chaos ensures that the whole process isn’t televised, as was seen during the passing of the farm bills. Accountability, on the other hand, is sacrificed, as constituents are eluded on the information as to the decision of their elected representatives. Thus, the right to information of the public by their public functionaries, as upheld in State of U.P. v. Raj Narain, cannot be exercised.

Another important aspect of the Parliament as mentioned in the Constitution that is being undercut is ‘bicameralism’. Historically, the Rajya Sabha has been one to prove as an obstacle in the passage of a bill, thus ensuring that the checks and balances scheme of the constitution is followed. But the usage of this practice to overrule the upper house, even when not having a majority assent, is an indirect violation of this principle, and thus the true interest and will of the people is defeated.

Relief by the Judiciary

Any relief from the Judiciary in this instance cannot be expected as the courts themselves have in cases such as Sanjay Lakhe Patil v. Haribhau Bagade, Janardan Reddy v. State of Hyderabad and many others, refused to entertain pleas challenging them, for want of Jurisdiction. This is by Articles 122 and 212 of the Indian Constitution, which provides immunity from Judicial Review to any irregularity in ‘any proceedings’ in the Parliament and the Legislature of a State respectively. Both these articles were passed without any debate in the Constituent Assembly. This becomes an important stance regarding the separation of power conundrum. This stance of courts has always been clear, wherein no irregularity of procedure can be called into question by review, bringing them into the special jurisdiction of the legislature, as held in Pandit M.S.M. Sharma v. Dr. Shree Krishna Sinha and Others.

But these articles must be interpreted keeping in mind the Keshav Singh Case (In Re: Special Reference No. 1 of 1964), which observed that a challenge against the validity of any proceedings inside the Legislature would only be possible if the said proceedings suffer not from mere irregularity of procedure, but from a substantive illegality. The aforementioned process isn’t merely a procedural irregularity as an undemocratic process goes clearly against Article 100 of the Constitution which necessitates a majority as well as all the prescribed Rules of the houses under Article 118(1) wherein the premise of all rules are the passing or failing of a bill on a discernible majority. Thus, when there isn’t a clear majority due to demonstrations disrupting such proceedings, there is a major substantive illegality in the process.

But this particular interpretation has not been settled yet. The recent Roger Mathew v. South Indian Bank case has resurfaced the debate on judicial scrutiny. Judges emphasised the dangers of a blanket exemption, warning that it could lead to deviations from constitutional provisions governing Parliament’s functioning and legislative procedures. The case posits the unresolved nature of using a voice vote during protests, calling for closer scrutiny to define the boundaries between the judiciary and the legislature. The case is now referred to a 7-judges bench for further deliberations on the ambit of legislative procedures.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

These practices go directly against the constitutional morality envisaged by Dr. Ambedkar. Even in Natural Law theory, there is the underlying principle of “minimum goodness” that all laws must possess. This stems from constitutional legitimacy within natural law that concerns how we make laws, and not what laws we make. This minimum goodness, in the Indian context, can be said to be in reference to the Basic Structure Doctrine and the Preamble. Thus, equity in the procedure of legislating is also an important part of the said doctrine.

Moreover, the Speaker should be pressing on the fact that whenever there is a challenge to the bill, the proper procedure must be utilised, ultimately leading to a division of votes that clears the Assembly of any ambiguity or partisan outcome. This discretionary power, further, must be subjected to judicial review to ensure constitutional adherence and to avoid the situation wherein an individual has unchecked power to carry out such constitutional subterfuge.

Specific mechanisms are essential to be utilised here to prevent the practice of voice voting amidst disruptions and act in a remedial capacity. Firstly, a clear-cut amendment on the lines of such interpretation that the voice-vote only be held whilst there is ‘a majority discernible consensus based on the conclusion of the Debate’ prefix should be inserted that would not give recognisance to such orders or bills passed. Secondly, the judiciary should, under its powers of review, more actively engage on the insistence of procedural adherence and accept and entertain PILs regarding the same, if not suo-moto cognizance on the knowledge of the same. Hence, these methods, inter alia, are imperative to uphold the true spirit and essence of democracy.

The authors are students at Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow

Image Credits: The Times of India

Leave a comment