Justice, in the Indian criminal system, is based on the idea of balance of rights of the accused and the state’s interests. Inclusion of procedural safeguards in the erstwhile Code of Criminal Procedure (hereinafter, “CrPC”) are proof of the legislative intent to protect the rights of an individual guaranteed under Articles 21 and 22 of the Indian Constitution (hereinafter, “the Constitution”). Section (hereinafter, “S.”) 167 of the CrPC is one example. Originally, the provision expected the completion of the investigation within 24 hrs (or 15 days at the permission of the Magistrate) regardless of the nature of the offence, when CrPC 1898 was enacted. However, the legislature understood the practical difficulties of this time-limit for completing investigation, it was extended to 60 days in 1973. This came after the 41st Law Commission’s recommendations. The 1978 amendment to S. 167 further altered the timeline for completing investigations. It extended the period to 90 days for offences carrying a punishment of death, life imprisonment or a minimum of 10 years of imprisonment, and to 60 days for all other cases.

After 1978, the provision has seen a change for the first time now in the new criminal law- the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (hereinafter, “BNSS”). S. 167 was reintroduced as S. 187 of the BNSS. The first proviso, the law in question, was reproduced as sub-section 3 of the new section. An omission of mere 7 words has significantly altered the substance of the provision in the BNSS, marking a departure from the protective framework envisioned under the CrPC, and diluting the procedural safeguard originally intended to uphold individual rights of the accused.

Legislative Intent Behind the Limit on Police Custody

Shri Ram Niwas Mirdha, as a Member of Parliament, played a key role during the legislative debates. He served as the Minister of State for Home Affairs when the CrPC was being formulated, contributing to its structure and focus on procedural fairness and efficiency in criminal justice. He had talked about the objective, or more to as to what is not the objective of this provision, in the parliamentary debate– “Even a reading of the present clause would suggest that it was never the intention that a person should be kept in custody for more than 15 days.”

In Rakesh Kumar Paul v. State of Assam, the Supreme Court of India (hereinafter, “SC”) analysed the basic legislative intent behind S. 167. It noted that even though the provision has been amended and extended over the years, the objective of ensuring a time-bound period remains unchanged. The legislature has always given paramount importance to personal liberty and “has always felt that it would be unfair to an accused to remain in custody for a prolonged or indefinite period.”

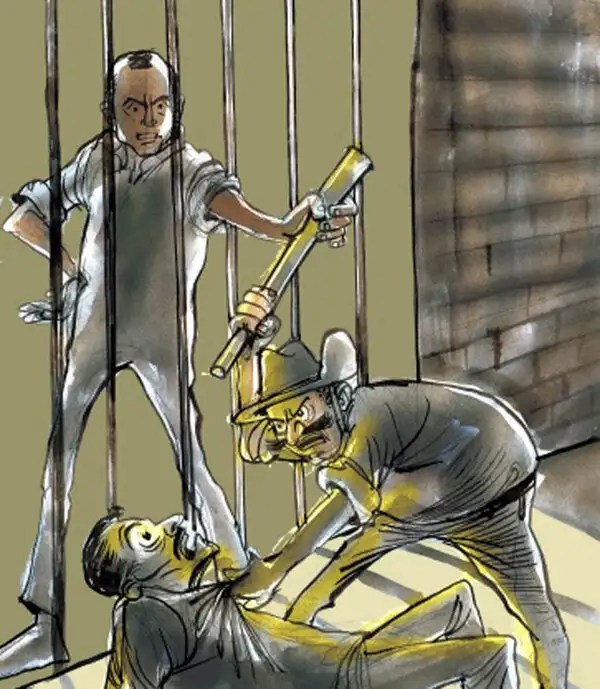

The apex court has time and again held detention beyond the period of 15 days, in the police custody, as illegal. Both the lawmakers and the courts have generally disfavoured police custody since it allows scope for curtailment of liberty and dignity of the accused by the actions of overzealous and unscrupulous police officers. In Satyajit Ballubhai Desai v. State of Gujarat, the SC held that police remand is an exception and not the rule. The aim of the police should be to complete investigation within 24 hours of remand and only if the Magistrate is convinced of the need of extension of detention, should it be allowed. The sole reason for it is protection from custodial violence.

In Mantoo Majumdar v. State of Bihar, the court held that remand orders should be passed not as a routine or process but after careful application of mind. A mechanical application or routine of authorising detention will do away with the constitutional mandates and obligations to protect the liberty and dignity of the people. In the landmark judgement of D.K. Basu v. State of W.B., the SC said that “Custodial death is perhaps one of the worst crimes in a civilised society governed by the Rule of Law. The rights inherent in Articles 21 and 22(1) of the Constitution (are) required to be zealously and scrupulously protected.” SS. 53, 54 and 167 of the CrPC are aimed at enforcing procedural safeguards to persons arrested by the police. D.K. Basu also laid down guidelines of investigation. These are a set of 11 procedures and requirements that the police and other agencies must follow when arresting, detaining, and interrogating a person. Police custodial torture cannot take place in isolation. It is the result of loopholes in the procedure established by law and the constant lack of reforms to correct these grey areas.

Protection of Accused’s Rights

The primary purpose of S. 167 was to safeguard the accused from potential misuse by overly zealous and unethical police officers. Both S. 57 of the CrPC and Article 22(2) of the Constitution underscore this intention. As a result, it is the duty of the Magistrate to thoroughly review the circumstances and, if convinced, authorize the detention of the accused in police custody. The intent and such stringent methods of allowing extension of police custody is that it should be limited as much as possible. The legislation has even disfavoured the prolonged period of judicial custody (by the way of the concept of default bail under the S. 167). The SC, in a 2-judge bench, in Central Bureau of Investigation v. Anupam Kulkarni, explained the scheme and legislative intent of the lawmakers and explained the rationale behind the limit on custody, which was to protect individuals from overzealous and unscrupulous police officers. This was further upheld by a 3-judge bench inBudh Singh v. State of Punjab. The change of the corresponding provision in BNSS thus, can be seen as an attempt to nullify Anupam J. Kulkarni.

A contrary view was taken in CBI v. Vikas Mishra and Sukhwinder Pal Bipan Kumar v. State of Punjab which observed that Anupam J. Kulkarni required reconsideration. With S. 187 BNSS, the reference to a larger Bench becomes infructuous as now the legislature has itself dealt with this issue. This is because the limitation has been removed from BNSS. Police custody may now extend even up to 90 days Under the CrPC, the legislative design sought to place firm limits on the duration of police custody, recognizing that prolonged detention without judicial oversight could infringe upon an individual’s fundamental rights. This reflected a clear commitment to protecting personal liberty by ensuring that investigative powers remained within constitutional bounds. In contrast, the BNSS marks a significant departure from this approach by permitting police custody for a period extending up to 90 days. This substantial increase in permissible custody duration weakens the earlier safeguards and shifts the balance in favour of investigative convenience over individual rights, thereby undermining the core protective intent that previously guided the law. Further, the words “such custody” as deemed fit is vague and can lead to various interpretations and inclusions of several kinds of custodies which can be allowed under this provision. These could include staggered police custody across non-consecutive days, intermittent shifts between police and judicial custody, or even innovative forms of quasi-custodial arrangements, depending on how courts interpret the term.

Dangers of a Prolonged Period of Police Custody

An important issue with the prolonged police custody is the reliability of evidences it produces in the form of confessions. Courts have routinely disregarded such disclosures as being involuntary and coerced. A prolonged period increases the likelihood of police pressure and can lead to coercion and therefore, unreliable evidences/confessions.

Another issue can be understood by understanding the period of custody given in the UAPA, which is a special legislation dealing with grave offences like organising a terrorism training camp. The duration of police custody permissible under UAPA is only thirty days. To this, there is a stark difference in the BNSS, which is a general criminal law and due to the lack of clarity on the kind of custody allowed in an extension, allows for police custody up to 90 days.

Way Ahead & Conclusion

One of the most important objectives of replacing the CrPC with the BNSS was the “suraksha (protection)” of individuals from the loopholes in the current criminal law system of justice delivery. This protection refers not just to the victims but also the accused. Procedural rules are meant to serve justice and not hinder it. The lawmakers aimed, with BNSS, to simplify the law and increase efficiency. While most of the new law is a reproduction of the erstwhile CrPC, some simple additions and omissions are changing the fate of numerous lives every day, with the application of the new laws.

Now, the question that arises at this juncture is what can be done. Should the new legislation be amended? The most practical way to resolve the arbitrariness of this provision is by the courts putting restrictions and restrains on the interpretation of the statute. In Commissioner of Income Tax v. M/s Hindustan Bulk Carriers, the Court held that statutory provisions have to be interpreted in such a manner that they are workable in nature. Further, the interpretation of a statute cannot be such that it leads to arbitrary and unconstitutional decisions. Therefore, the Apex Court must limit the interpretation and meaning of “custody” in the context of this provision, this would bring the law back to the position under the Code. However, what should also be mentioned in the same breath is the best possible solution to this arbitrary and unconstitutional new law- a parliamentary amendment. This is necessary to prevent any further miscarriage of justice and failure of constitutional principles, than it already has, since it’s enforcement earlier last year on 1st July 2024.

S. 187(3) BNSS poses a significant challenge and risk to fundamental rights and the principles of justice enshrined in the Indian Constitution. Prolonging police custody up to 90 days undermines the legislative intent of limiting detention periods to protect personal liberty and prevent custodial abuse. To address these issues, the judiciary must interpret the statute in a manner that preserves constitutional mandates, and a parliamentary amendment is essential to rectify arbitrary and unconstitutional provisions. Articles 21 and 22 of the Indian Constitution play a pivotal role in safeguarding individual liberties and ensuring due process. Procedural safeguards under S. 167 of the CrPC, designed to balance state power and personal liberty, have been weakened, raising concerns about the erosion of the right to fair treatment.

The Author is a fourth year student of National Law University Odisha

Image Credits: Times of India

Leave a comment