Introduction

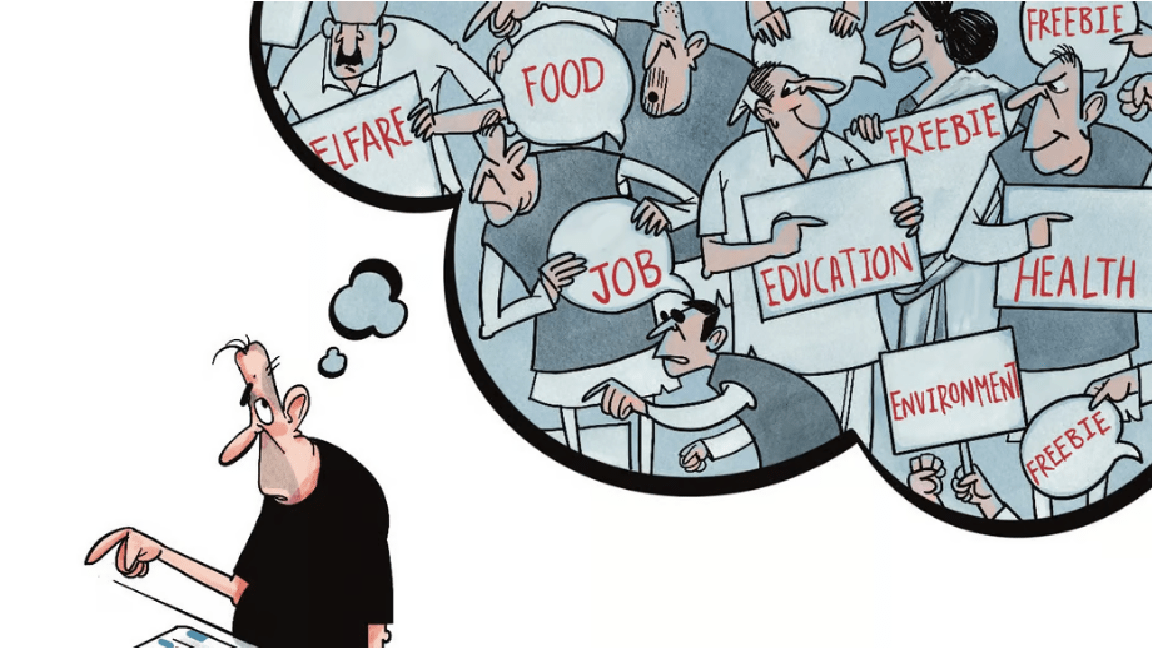

The 2024 general elections witnessed a curious debate around freebies in electoral democracies. The results, which paved the way for a coalition government and a split verdict, present contradicting perspectives on freebies. While one view suggests that the reason behind the resurgent Indian National Congress was the promise of freebies, the other opines that the Indian electorate has unequivocally rejected the idea their vote can be purchased through promises. This has occurred even as fiscal prudence and policy continuity were two major concerns for economists.

This battle, however, is not restricted to politics alone. Ashwini Upadhyay, a lawyer associated with the BJP, filed a Writ Petition (“Ashwini Upadhyay”) in the Supreme Court (“S.C”) contending that the promise of distribution of freebies before elections shakes the roots of free and fair elections and vitiates the purity of the electoral process. Multiple opposition parties have also joined the case in their capacity as intervenors, including the Aam Aadmi Party and the DMK. On a first-hand inspection, it would appear as though Ashwini Upadhyay is merely an attempt at reconsideration of Subramaniam Balaji (2013); however, while the latter principally dealt with the problem of electoral influence, the former also deals with the broader issue of how freebies can undermine public finances. As part of answering the many questions in Ashwani Upadhayay, the judges of the S.C will traverse a thin line between judicial restraint and judicial intervention. Firstly, this article will deal with two major problems associated with the petition. Thereafter, the article will advocate the need for a non-uniform solution that is representative of the states’ unique economic capacities. The article will deal with why the S.C is best positioned to deal with the issue of freebies in electoral politics and finally it will expound on the concept of irrationality, arguing for enlarging the scope of irrationality of freebies.

The fundamnetal problem in defining freebies

In Ashwini Upadhyay, the petitioner has prayed for the direction that the promise of irrational freebies before elections be made analogous to bribery and undue influence. Such a directive, whether issued by the central government or the judiciary, suffers from the same problem of defining what constitutes a freebie. The concept of freebies, being closely related to social welfare schemes, is subject to infinite manipulation. Different individuals and different organisations prefer their definition for the concept of freebies. The, RBI, for instance, holds even the grant of free public transport as a freebie. Such a definition, for instance, ignores both the environmental benefit associated with public transport and the economic benefit of greater participation of women in the workforce. Other definitions, such as those based on “merit goods” and “public goods”, also have their own drawbacks.

In Ashwini Upadhyay, it is assumed that freebies are divorced from the idea of development and that money alternatively spent on infrastructural activities like the construction of dams and lakes is more appropriate. Former President Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam had remarked that the idea of development was to be judged according to a national prosperity index, which is determined not only by GDP growth but also by improvement of the quality of life of people below the poverty line and the adoption of value systems unique to India. It would, therefore, be hard to contend that schemes such as the distribution of cycles to children or women coming from families below the poverty line do not lead to upliftment and, hence, the development of the nation. Given the lack of consensus on what constitutes freebies, any judicial intervention could prove to be anti-democratic, anti-poor and anti-constitutional.

De-registration of political parties: A recipe for conflict

Secondly, the petitioner in Ashwini Upadhyay has prayed for the Election Commission of India to be given the power to de-register political parties if they promise to distribute irrational freebies from public funds. This would not only be a recipe for conflict between the Election Commission and political parties but would also require a relook into the regulation of election manifestos by the Election Commission of India. An election manifesto is “a public written declaration of the intentions, opinions or motives of a leader, party or body.”.[i]A manifesto, therefore, serves as a benchmark for the public at large to judge the political party and its stance. When the S.C announced its verdict in Subramaniam Balaji and allowed the schemes of the Tamil Nadu government, it also ordered the Election Commission to frame certain guidelines regulating the promises of political parties. As a result of this instruction, the Election Commission inserted guidelines into the moral code of conduct after discussion with stakeholders, including the then-opposition parties. Even before the guidelines were decided, the verdict of the S.C was criticised then for increasing regulation in manifestos. For instance, it was contended that the very purpose of a manifesto in an electoral democracy is to influence voters and win support. Then, appointing an agency to regulate the promise of an electoral manifesto would be unbecoming of democratic norms. To add to this criticism, the biggest regulator, the Indian electorate, also seems to be catching on to the problem of freebies.

Whether it is the Prime Minister’s clarion call or the informed Indian electorate’s aversion to freebies, the current scheme of things appears to be working with little need for the de-registration of political parties. It is more important for the Election Commission to ensure enforcement of § 123 of the Representation of People Act, given several instances of cash for vote being observed in the assembly and general elections.

Need for a non-uniform approach

Freebies are undesirable in any democracy, not only because they might vitiate the purity of the electoral process but also because of the fiscal stress they might cause. The S.C has already recognised this in Subramaniam Balaji (¶ 77). Senior Advocates appearing for opposition political parties have also argued for distinctions to be drawn between the concept of freebies and social welfare schemes. The problem at hand, therefore, is that a blanket ban on freebies might prevent legitimate social welfare schemes from reaching the public.

The issue of freebies is not as simple as the ruling party versus the opposition. Firstly, the centre is also equally guilty of providing freebies in a few instances, as pointed out by Senior Advocate Prashant Bhushan. Secondly, certain states are better placed to offer welfare schemes as opposed to others. Delhi, for instance, can afford more expenditure on welfare schemes by virtue of the fact that many bills of the state are paid by the centre. What this implies is that rich states can offer more schemes than poor states. Therefore, what might be a freebie for one state might not prove to be a freebie in the context of another state. If a state hence continues to increase its spending on social welfare to match another state without a commensurate increase in revenue, its economy will suffer in the long run. The problem of freebies, therefore, might need a non-uniform solution keeping in mind the unique characteristics and economic capacities of various states.

Why the buck must stop with the Supreme Court

Historically, the S.C has refrained from interfering in policy decisions, which might result in cascading effects. On the second day of hearing Ashwini Upadhyay, the former Chief Justice of India, N.V. Ramana, had already expressed his hesitance to intervene in policy considerations. This is not particularly unexpected, especially given that the S.C has previously cautioned judges against encroaching into the executive or the legislature. Several academicians and research institutes have also weighed in their support for a laissez faire approach, choosing to place their trust in the judgement of the Indian electorate. However, given present-day circumstances, where parliamentary debate is a dying trend, judicial activism has become an essential aspect of constitutional courts. Given the repercussions of leaving freebies unchecked, the need of the hour is to find a definitive solution to the problem of economic ruin that can be caused by freebies. The S.C has already attempted to assign this task in the past to the Election Commission of India after Subramaniam Balaji, but evidence indicates that their guidelines have hardly been useful in solving the issue at hand. In addition, the opposition’s trust in the independence of the Election Commission of India has been at an all-time low. It would also be immature to expect all political parties to agree in principle on the issue of freebies, especially given that they might derive support from such promises.

In such circumstances, the SC offers the possibility of framing an apolitical opinion that would bind together all stakeholders. Most definitely, the SC’s duty is not to serve as parliament to facilitate and formulate regulations, but at a time when the parliament becomes dysfunctional, more and more Indians look to the SC as their last hope.

Expounding the concept of Irrationality

Petitioners who challenge the issuance of freebies have preferred to use the catchall phrase of ‘irrationality’ to sustain their attack. As already discussed in Part II there exists a fundamental problem of defining freebies wherein each side attempts to prove and disprove that schemes are rational and irrational. Rationality is a subjective concept, Afterall even the S.C has recognised the same in Subramaniam Balaji while holding that distribution of colour Television Sets, grinders, etc could not necessarily be categorised as wasteful expenditure in the 21st century. Prima facie, this observation is undoubtedly correct but in light of development concepts such as sustainable development it is important to reconcile the needs of the present generation with that of the future generation. To add to this, freebies such as subsidies also distort prices and encourage wasteful utilisation. Therefore, interpretating irrationality narrowly would only do injustice to the future generations who would suffer the impact of excess fiscal deficit and limited resources left behind by their forefathers. Hence, it is imperative to devise a more astute concept of irrationality, one that gauges schemes more effectively and does not shy away from striking down those that excessively burden the fiscal strength of the state.

Inadvertently, it is submitted that the best way to trim down on state largesse is to reconsider the ratio of the court in Subramaniam Balaji where it was held that such measures were connected with the implementation of Directive Principles of State Policy (‘D.P.S.P’) and therefore could not be tested against Article 14. Testing such schemes against the touchstone of Article 14 can pave the way for more targeted schemes that would actually go far to achieve the socialist ideals of the constitution that aim to reduce inequality in the society. In Subramaniam Balaji (¶70), the argument was refuted on the ground that, state largesse is associated with D.P.S.P and can be challenged only on the ground that it imposes some burden on citizens financially or otherwise. Undoubtedly, it is the state exchequer which funds such schemes, but the funds are really derived from diligent taxpayers who would prefer accountability in government spending (application for intervention by Tax Payers Association of Bharat). Reckless spending without any checks and balances would hence no doubt burden citizens financially by subjecting them to greater taxes and inflation. By granting supremacy to DPSP’s against the fundamental right of Article 14, the SC had failed to carry forward the decision of the constitutional bench in Minerva Mills, thus necessitating the need for a relook.

Conclusion

The S.C had advocated for a hands-off approach amidst the elections. With the general elections concluded and campaigning taking a pause, the S.C is now free to continue hearing the challenge to freebies. As part of hearing arguments, the court must look for innovative solutions that seek to balance fiscal prudence and the constitutional objectives of welfare, keeping in mind all relevant.

Undoubtedly, the petitioners in Ashwini Upadhyay face several challenges to prove their case. The verdict of the S.C, as always, will undoubtedly be subject to criticism. After all, even a judge is a citizen and is bound to have political preferences. However, as S.P. Sathe observes, “a judge can be non-political in the sense that his decisions are based not on considerations of power, but rather on principles”. Quite possibly, this underlying principle could open the pathway to an activist judiciary that is no longer hesitant to intervene in economic matters for the greater public good.

Endnotes:

[i] P Ramanatha Aiyar, Advanced Law Lexicon–The Encyclopaedic Law Dictionary with Words & Phrases, Legal Maxims and Latin Terms: Manifesto 3388 (Lexis Nexis 6th ed. 2019).

The Author is a 2nd-year student from Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University, Visakhapatnam

Image Credit: TNIE

Leave a comment