Priyam Mitra

Introduction

“The Indian Constitution has not indeed recognised the doctrine of separation of powers in the absolute rigidity, but the functions of the different parts or branches of the Government have been sufficiently differentiated and consequently it can very well be said that our Constitution does not contemplate assumption by one organ or part of the State of the functions that essentially belong to another.”

– Chief Justice B.K. Mukherjea (in Ram Jawaya Kapur)

The doctrine of Separation of Powers has managed to capture the imaginations of several scholars, Montesquieu, the French jurist being the modern exponent of the same. In his seminal work, The Spirit of Laws, published in 1748, Montesquieu notes how the legislative, executive, and judiciary powers, must categorically function in separate spheres, for “all would be lost if the same man or the same body […] exercised these three powers.” Various jurisdictions, including India and the United Kingdom, have stayed away from adopting such a rigid separation of powers.

The Indian Constitution has indeed adopted the British model of parliamentary government with the President (analogous with the British Monarch) as the Constitutional head of the Executive. However, clarifying the ministerial character of the Executive, the Constitution drafters and the courts later have held the view that the President has no ‘real powers’ and that the real executive powers lie in the hands of the Council of Ministers. The seminal judgement of the Supreme Court in Ram Jawaya Kapur v. State of Punjab (1955), posits that in such systems, the executive and the legislature are closely entwined as the executive also commands a majority in the Parliament and is therefore assumed to have the tacit support of the legislature in policy formulation. The reason for not strictly separating the two is purported to greater stability and efficiency in government; a scholar remarks how such a system “intentionally promotes efficiency over abstract concerns about tyranny.”

The paper primarily seeks to demonstrate how adoption of such a conception of separation of powers is not as unproblematic as it seems and carries with it a real possibility of skewing the balance of powers away from the legislature and towards the executive. With the backdrop of 70 years of Ram Jawaya Kapur, the paper first critically evaluates the landmark judgement pronounced in the case of Ram Jawaya Kapur v. State of Punjab, (1955); secondly, it looks at legislative undermining in two parts- i) majority governments and ii) coalition governments; finally, the paper concludes by looking at avenues for strengthening the oversight on executive functions.

Ram Jawaya Kapur (1955)- Circumscribing Executive Power

Before looking at the judgement delivered in Ram Jawaya Kapur, it is pertinent to briefly discuss the debates in the Constituent Assembly with respect to the power distribution between the legislature and the executive. This exercise is helpful not only to clarify why the separation of powers was envisaged as it was, but also because it serves as the backdrop of the landmark judgement delivered just five years after the enactment of the Constitution.

Three interdependent, though seemingly varied reasonings, garnered support in the Constituent Assembly. K. Santhanam echoed the need for efficient governance as the reason for an integrated conception of the Parliament and the Centre Government. The specific economic condition of India at Independence was also a consideration in arriving at this reasoning. To ensure economic progress, it was necessary to reduce the scope of conflict between the Parliament and the Executive. K.M. Munshi posited that since the Cabinet functioned with the support of the majority of the Parliament, there could be no conflict between the legislature and the executive. For Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, it was necessary that the executive guided the legislature since the work of the Parliament was so complicated and vast that without the initiation by the executive, it could not function effectively.

All three arguments find their place in the reasoning of the court in Ram Jawaya Kapur as would be shown below. The relevant issue vis-à-vis the separation of powers was whether an action by the executive was permissible without a prior legislative sanction.

The Supreme Court clarified that executive powers have not been exhaustively defined in the Constitution and that Article 73 empowers the executive to exercise its powers on matters upon which the Parliament is empowered to legislate. The court held that Article 73 in no way confines the powers of the executive to only matters upon which there is a legislation already passed. The court, while refraining from exhaustively defining executive functions, did enlist some constraints on executive powers. The Constitution does not envisage a situation wherein the executive (without legislative sanction) undertakes a function of any other organ, or goes against any provision of any law, or encroaches upon private rights.

The rationale behind the judgement’s ratio stems from the arguments discussed in the Constituent Assembly (though they have not been explicitly cited). The court echoes the sentiments of Dr. Ambedkar and Pandit Nehru by holding that the real executive powers are vested in the Cabinet and hence they have the responsibility of both determination of policy and execution of the same. The court highlights the famous quote of Bagehot, “the Council of Ministers is like a hyphen which joins, a buckle which fastens, the legislative part of the State to the executive part”. K.M. Munshi’s contention too finds its place in the court’s reasoning when the court states that the cabinet virtually controls both the legislative and executive functions. The underlying principle in all these reasonings is that of collective responsibility of the cabinet.

While the ratio in the case seems to be in consonance with what was the intent of the Constituent Assembly, the subsequent sections would try to posit how theoretically (and also to a certain degree empirically) such a conception of separation of powers could lead to legislative minimization and in turn “executive aggrandizement” (a term coined by Nancy Bermeo). This problem would be shown to stem from the hopeful conception of collective responsibility of the cabinet to the Parliament.

Executive Aggrandizement and Legislative Minimisation

In any parliamentary democracy, the executive is the branch which wields the sword of power and hence there are mechanisms put in place for the purposes of accountability. Certainly, the Constituent Assembly of India too recognized this and thereby inserted Article 75 (3) which makes the Council of Ministers accountable to the House of People. The oversight function of the legislature in ensuring transparency, accountability and safeguarding democratic governance manifests itself in three ways-

1. The Prime Minister is the first among equals- this eminence granted to her comes with the pre-condition that all cabinet ministers are accommodated wisely and are kept in the loop. The ministers must have collective responsibility; in public at least, the cabinet must take responsibility for their collective actions.

2. Ministers have to constantly face criticism through parliamentary questions- this keeps them abreast of the larger opinions of the people.

3. The executive regulates the functioning of the legislature to a large extent, however, measures such as question hour, motions and legislative committees are helpful in ensuring accountability.

Majority Governments

A theory of the Executive slowly withering down such accountability measures has been propounded by Nancy Bermeo. Executive Aggrandizement as defined by Bermeo is a gradual from of ‘democratic backsliding’ wherein the legitimately elected executive seeks to weaken the institutional framework of checks and balances, including the legislature, the judiciary and other fourth branch institutions. Legislative accountability, by virtue of it being elected, has to be exercised by the political opposition. The phenomenon of executive aggrandizement is exercised through legal channels and hence a weakened opposition, by way of electoral failures and internal divisions, provides a fertile ground for the same.

Tarunabh Khaitan exceptionally outlines how such a process could be seen synthesizing in post 2014 India. The threat to an elected democratic regime comes from within, the elected executive’s interests lie in securing votes in the next election cycle and towards this end, the executive circumvents the institutional mechanisms of checks and balances as elucidated before. Khaitan calls the legislature (and other fourth branch institutions) as comprising the horizontal axis of accountability. In the case of a majority government, as the BJP attained in the 16th Lok Sabha Elections, with a weak opposition in the legislature, the executive regularly diminished the role of the legislature by avoiding many of the accountability measures.

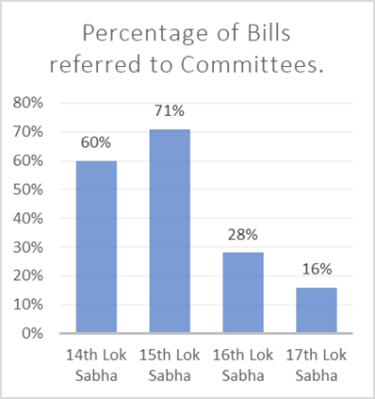

Since the role of the cabinet also involves the initiation of legislation, the executive has the power to slyly minimize legislative scrutiny in several ways. For example, the BJP Government has been alleged to regularly employ an extraordinary parliamentary procedure known as the ‘guillotine’. Through such a procedure, the Speaker of the House puts the bill to vote, without any discussions. Two such instances include the passing of a 2018 Finance Bill and the interim budget of 2019; this was done among opposition protests and suggestions for amendments. This is uniquely possible only when the executive is confident of its legislative majority abiding by party duties; this effectively converts the Legislature into a ‘registering chamber’ of the executive decisions. Figure 1 confirms this lack of deliberation in the legislature as the average time spent on important bills like the Budget has been consistently dwindling, the lowest being in the 16th Lok Sabha.

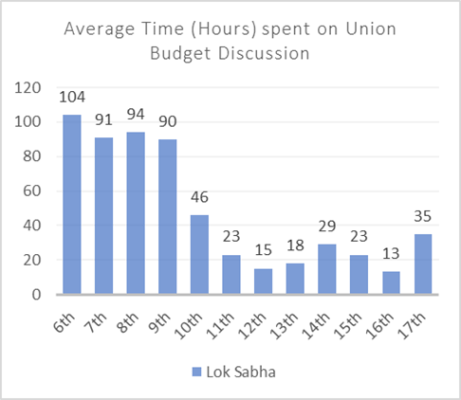

Another important mechanism for accountability of executive policies, is the employment of parliamentary committees for the purposes of scrutinizing and suggesting changes to bills. Figure 2 shows how the percentage of bills referred to committees was as high as 71% in the 15th Lok Sabha. With the singular majority in the 16th Lok Sabha, this figure was minimized to 28% and in the 17th Lok Sabha, with an even stronger legislative majority, the figure further dropped to 16%.

While the legislative’s role has been diminished, this has been observed in tandem with an increase in executive powers. Khaitan painstakingly outlines how this eventualizes in several spheres including the judiciary, appointment in fourth branch institutions, the media etc., However, the relevant part of his critique for this paper is how the Cabinet is itself not shielded from the effects of a majority government. It is important to note that the judgement in Ram Jawaya Kapur, was delivered in 1955, when it was easier to assume a unison of the cabinet and the legislature in the absence of any real political opposition. In contemporary times, a resignation letter from Upendra Kushwaha shines light on the opaque working of the cabinet. He alleges the Prime Minister as forcing his decisions on the Cabinet, reducing it to a mere ‘rubber stamp’. Assuming that the Cabinet has a collective vision for policy formulation is even more suspect when we consider the various factions that constitute the Cabinet in coalition Government.

Coalition Governments

The reason why a Cabinet is much more fragmented, at least ideologically, is because ministers find themselves at the crosshairs of two competing principles– their legislative party and the parliamentary majority constituting the executive. While they contribute in concerted efforts vis-à-vis policy determination, they simultaneously compete with their coalition partners for electoral votes. Though several scholars including Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C Muller and Daniel Markham Smith, have centred their analysis in Europe, the paper argues that similar notions of fragmented coalition ministers are found in Indian history.

K.T. Shah, in the Constituent Assembly Debates echoed the possibility of a ‘spoils system’ wherein individual members of the Legislature could be swayed by the grant of offices and ministries. In a coalition government, when one party has considerable control on a ministry, there is considerable scope of ‘hidden action’. In such a situation, it could not be realistically said that the Cabinet is united in its purpose and that they must maintain a ‘collective responsibility’. Dr Bimal Jalan (former Governor of the RBI) [endnote 1] notes such an instance from 2004 wherein a Ministry, devoid of any discussion with the Cabinet or a debate in the Parliament, executed an order reducing the financial autonomy of the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs). The appointed minister, after 2004 elections, reversed this decision. Jalan further remarks how sectional interests within the domain of coalition politics, coupled with independent executive power can result in orders which reflect short term electoral interests rather than the long-term interests of the nation.

The legislative arena serves an important purpose, at least theoretically, for coalition partners to seek accountability from each other. Parliamentary questions and legislative committees, bestows upon the legislative members the power to oversee the functioning of the Coalition Cabinet. This also helps in addressing any rogue ‘hidden action’ by any minister. However, as already noted before, these practices of the legislature have been cleverly circumvented by various Governments (Figures 1 and 2). In coalition politics, it is the extra-parliamentary arena that gains prominence as a site for fostering consensus. The primary reason for its centrality is that it provides a separate arena for deliberation which helps alleviate fears over electoral fallout. Indeed, Indian history of coalition politics also has the formation of ‘Coordination Committees’ as a key method of integration without the glare of the public. Its necessity is evidenced by its presence in every coalition government since 1996. Parliamentarians in the 1990s, in the wake of extra-parliamentary measures, often ignored executive’s poor drafting of legislation and discussions on important matters like the budget were also scarce.

Conclusion

After the discussion laid out in the preceding sections, it would not be strenuous to title the minimisation of legislative oversight and centrality as a ‘silent shift’ in the separation of powers. None of the ways in which the legislature has been side-lined is spectacular in any way. In either form of the Central Executive- a majority or a coalition, there have been different ways in which the accountability powers of the legislature were circumvented for different reasons- from ensuring minimum scrutiny of the executive to shifting the locus of deliberation for electoral reasons. Therefore, while the judgement in Ram Jawaya Kapur, cannot be called erroneous, it does become pertinent to inquire into whether the institutional safeguards provided for on paper, are being implemented on ground or not.

Khaitan provides for three tiers of accountability of the Executive- vertically, through direct endorsement of the people; horizontal, through the legislature, judiciary and other fourth branch institutions; diagonal, through civil society institutions. While reform in all these spheres necessitates itself, reform in some would be more plausible to realize. Independence of several of these institutions is averse to the functioning of most political parties, however, in a democracy, every party has (or should have) a fair chance of securing a legislative majority and therefore every party may find themselves in the shoes of a legislative minority. Therefore, through strengthening legislative measures such as budget discussions, questioning the executive, parliamentary committees and an independent speaker, the legislature can regain its necessary function of keeping a check on the executive in the democratic fabric.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Dr Bimal Jalan, Separation of Powers: The Myth and The Reality, Third Nani A Palkhivala Memorial Lecture (Nani A Palkhivala Memorial Trust, January 2006).

The Author is a second-year student at National Law School of India University, Bengaluru.

Leave a comment