Kamod Patel and Tarun Dev Singh

Introduction

In a constitutional democracy, access to justice is not just a legal formality – it is the lifeblood of the system. Without it, laws are hollow promises and rights mere rhetoric. In India, ‘access to justice’ is enshrined as a fundamental right under Article 21. There is an invisible price tag hanging on the courtrooms. The price, that is the court fee is significantly disproportionate across states, and can turn pursuit for justice into economic gamble for some. Perhaps, even more ironically, states with very low per capita income impose this regressive burden over the people that are the most marginalized and in need of judicial redress. Therefore, the question is, whether the court fee is really a ‘fee’, or is it more of a ‘tax burden’?

This paper seeks to analyse the development of court fees in India; the author investigates into the constitutional elements, and the empirical evidence that demonstrates the extent to which court fees have developed as a regulatory mechanism but which has now morphed into an exclusionary barrier. The paper has identified a need for reform, analysing inter alia, recommendations by various law commissions urging the necessity to rationalise and humanise the fee structure. Ultimately, it is necessary to ensure that the doors of justice remain open to all irrespective of their economic means, geographic location, or social status.

Nature And Purpose of Court Fees: Revenue or Justice?

Court Fees in India have had a dynamic history. The rationale behind levying Court fees has been largely influenced by evolution and expansion of human rights jurisprudence and the emergence of the welfare state. Whereas court fees was traditionally seen as a means of raising public revenue and deterring frivolous or vexatious litigations, their function and justification have evolved in light of competing concerns about access to justice and social equity.

The Court fee is a statutory obligation imposed through the Court fee Act, 1870. During the British era, court fees was introduced and it acted as a tool to offset the expenses incurred in administering the judicial mechanism. Procedural law makes the institution of suits conditional upon the payment of prescribed fee (Order VII, R11 CPC) lest it attract procedural sanctions including rejection of the plaint or other consequences under the Code of Civil Procedure. Likewise, the constitutional scheme and public policy (Article 39A) insist that, non-payment of the same said fee shall not bar access to justice. Though the state tried to strike a balance in the form of waivers or exemptions to the indigent, litigants on public service rolls, women, minors, SC/ST etc., yet significant gaps and uneven application persist.

The legal character of the court fee i.e., whether they are a tax or a fee is nebulous; the question is not merely a semantic one. It is necessary to understand its nature, so as to ascertain the (i.) legislative competence, (ii.) potential violation of constitutional aspirations (Art.39A) if it is in the form of tax, (iii.) Quid pro quo requirement (whether fee required satisfies reasonable nexus with the service rendered) and (iv) the scope constitutional authority to levy the same said charge.

The test to distinguish between the fee and tax was first laid down in the case of The Commissioner, Hindu Religious Endowments, Madras v. Sri Lakshmindra Thirtha Swamiar wherein the court applied a quid-pro-quo test, requiring that the levy must bear a direct relationship (nexus) to a service provided, thereto. In its later decisions culminating in Krishi Upaj Mandi Samiti v. Orient Paper & Industries Ltd., the Court refined the inquiry into a multi-factoral test looking into: (1) is the charge compulsory; (2) what is its primary purpose: general revenue or meeting the cost of a service; (3) who principally benefits: the public at large or identifiable users; and (4) is there a tangible link between the charge and a service rendered (quid pro quo test). Court fees are demanded as a precondition for invoking judicial process and services thereto, and are borne by the litigant who receives that service. Thus, on applying the tests to the court fees, it is evident that such charge is in the nature of ‘fee’ rather than tax.

A constitutional bench in Govt. of Madras v. Zenith Lamps and Electrical Ltd., held that “The very use of the words ‘not including fees taken in any court’ in Entry 96 List 1, and Entry 66 List 11 (which mentions the taxes the union and the state can levy) shows that they would otherwise have fallen within these Entries. Therefore ‘fees taken in Court’ cannot be equated to ‘taxes’.”

But Justice Chandrachud in a recent judgment observed that the practical and even constitutional distinction between a tax and fee has been weathered down. Fees may have the component of compulsion attached to it and its proceeds may be part of consolidated funds like taxes. It is hereby humbly urged that, although they are referred to as “fees,” ad valorem court charges, particularly those that are uncapped in low-income regions operate as a form of regressive impost on poor litigants. Where such charges fall disproportionately on low-income users, they produce an economic barrier to litigation that conflicts with constitutional commitments to access to justice. The analysis in the next part further bolsters this assertion of the author.

Access to Justice under Article 21: Constitutional, Global, and Empirical Perspectives

Access to justice is not just only a right in law, but rather a substantive right guaranteed within the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The courts have progressively interpreted the right of access to justice to assure that individuals not only have recognized legal rights, but also meaningful access to the enforcement of those rights. In the case of Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar, the Supreme Court determined that a speedy trial is part of the right to life under Article 21, stating that “It is the constitutional obligation of the State to provide free legal services to an accused who is unable to secure legal services on account of indigence”. Similarly, the Court established in Khatri (II) v. State of Bihar that, legal aid is not charity but a constitutional duty. The State’s obligation to provide legal representation access received further clarification through Anokhilal v. State of Madhya Pradesh where the Court established that Article 21 guarantees include procedural fairness and affordable legal representation and access to legal services.

Article 39A enjoins the State to ensure equal access to justice and free legal aid to all Indian citizens who face economic or other disabilities. Pursuant to that constitutional mandate, Parliament enacted the Legal Services Authorities Act of 1987 thereby creating a statutory framework for providing right to legal services for the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, women, children, disabled persons and other disadvantaged sections of society. Despite such legislative recognition, only few are eligible to access legal service. A report published by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy noted that only 2.36% of eligible litigants relied upon a court-appointed lawyer. This reflects a substantial gap between formal entitlements and access in practice.

India’s constitutional obligations align with the global human rights protocols. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), 1966 to which India is a signatory, stating in Article 14 that everyone has the right to a fair and public hearing and legal assistance whenever the interests of justice require. The UN Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers (1990) state that governments shall ensure that everyone has access to legal services provided by independent lawyers, notwithstanding their economic or social circumstances. Article 8 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) states that: “Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals.” These instruments create an obligation for states to ensure that legal systems are formal and functional for all.

In light of the same, the empirical data reflects the structural and financial burdens on Indian litigants. According to the India Justice Report (2024–25), there are only 15 judges for every million people in India, when there is a need to have at least 50 for every million people. There are currently over 5 crores cases backlogged, with more than 61% of matters in the High Court and 46% of matters in the district court pending for over 3 years. The economic consequences of the same are staggering. A 2020 report by the Vidhi Centre also noted that litigants incur an average of ₹520 daily to attend courts, providing a total estimated national litigation cost of ₹30,000 crore annually, as well as productivity losses worth ₹50,000 crore; almost 0.48% of the national GDP. For uniformly low-income litigants with a yearly income of less than ₹1 lakh, court appearances represent more than 25% of their annual income. These financial risks, paired with delays and poor legal aid funding means that access to justice is practically elusive for a vast majority.

A Tale of Unequal Burdens: Across Indian States

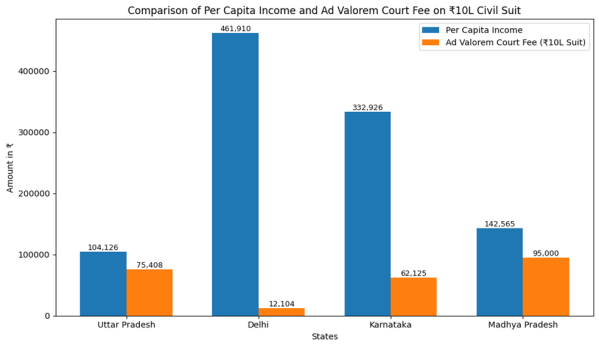

Per Capita Income and Ad valorem Court Fee (on a suit valuation of Rs. 10 lakhs)[i]

India’s court-fee regime erects significant barriers to access to justice: the Law Commission has aptly described this as a “postcode lottery.” For example, a ₹10 lakh civil suit attracts a fee of only ₹12,104 in Delhi, whereas Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh apply high ad valorem fees that can drive litigation costs into several lakhs.

The differences in court fees are producing “forum shopping”, opted by litigants with the resources who strategically choose favourable jurisdictions with lower costs, thereby demonstrating inequity of a most extreme kind. What exacerbates the situation is that, low-income states (UP, MP, Bihar) are charging fees which form a larger share of the local revenues. The evidence consistently suggests that, as a percentage of individual income, court fees are relatively higher, for litigants in UP (66%) than those in places like Delhi (just 2.6%), with the highest per capita income, if they brought about a suit having subject matter valued at Rs. 10 lakhs.[ii]

Therefore, such regressive pricing effectively silences the poor and deter bona fide claims by converting fees from modest regulatory instruments into prohibitive barriers. This erosion of access to justice disproportionately burdens low-income litigants and, in practice, defeats the constitutional commitment to equal justice under Article 39A. It is high time that India needs national-level rationalisation and a progressive, income-sensitive court fee regime.

Judicial concern over the exclusionary potential of court fees has also been expressed at the High Court level. The Kerala High Court in Kerala High Court Advocates’ Association v. State of Kerala, entertained a public interest challenge to the revision of court fees under the Kerala Court Fees and Suits Valuation Act and engaged with the argument that excessive court-fee structures may impair access to justice under Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. Similarly, the Guwahati High Court in Prafulla Govinda Baruah v. State of Assam, held that imposing ad valorem court fees without any upper limit is arbitrary and lacks a rational nexus with the cost of administering justice, thereby rendering such a levy constitutionally infirm under Article 14.

[i] Government of India, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, State-wise Net State Domestic Product (NSDP) per Capita at Current Prices, 2023–24; Court-Fees Act, 1870 (as applicable to Uttar Pradesh and the National Capital Territory of Delhi), Schedule I, art. 1; Karnataka Court Fees and Suits Valuation Act, 1958, sched. I; Madhya Pradesh Court Fees Act, 1870 (as amended), sched. I; calculations by the author.

[ii] Ibid.

The authors are a final year student and a penultimate year student of the Dharmashastra National Law University, Jabalpur.

Image Credits: Tingey Injury Law Firm, USA

Leave a comment