The next decennial census has been announced. It will be conducted in 2027 as per the Census Act, 1948 and the Census Rules, 1990. While the decennial census is conducted by the Central Government, there remain considerable confusion and debate regarding the competence of State Governments to conduct censuses or census-like exercises. The Supreme Court is currently hearing an appeal against the Patna High Court (‘Court’) decision in the case of Youth for Equality v. State of Bihar.

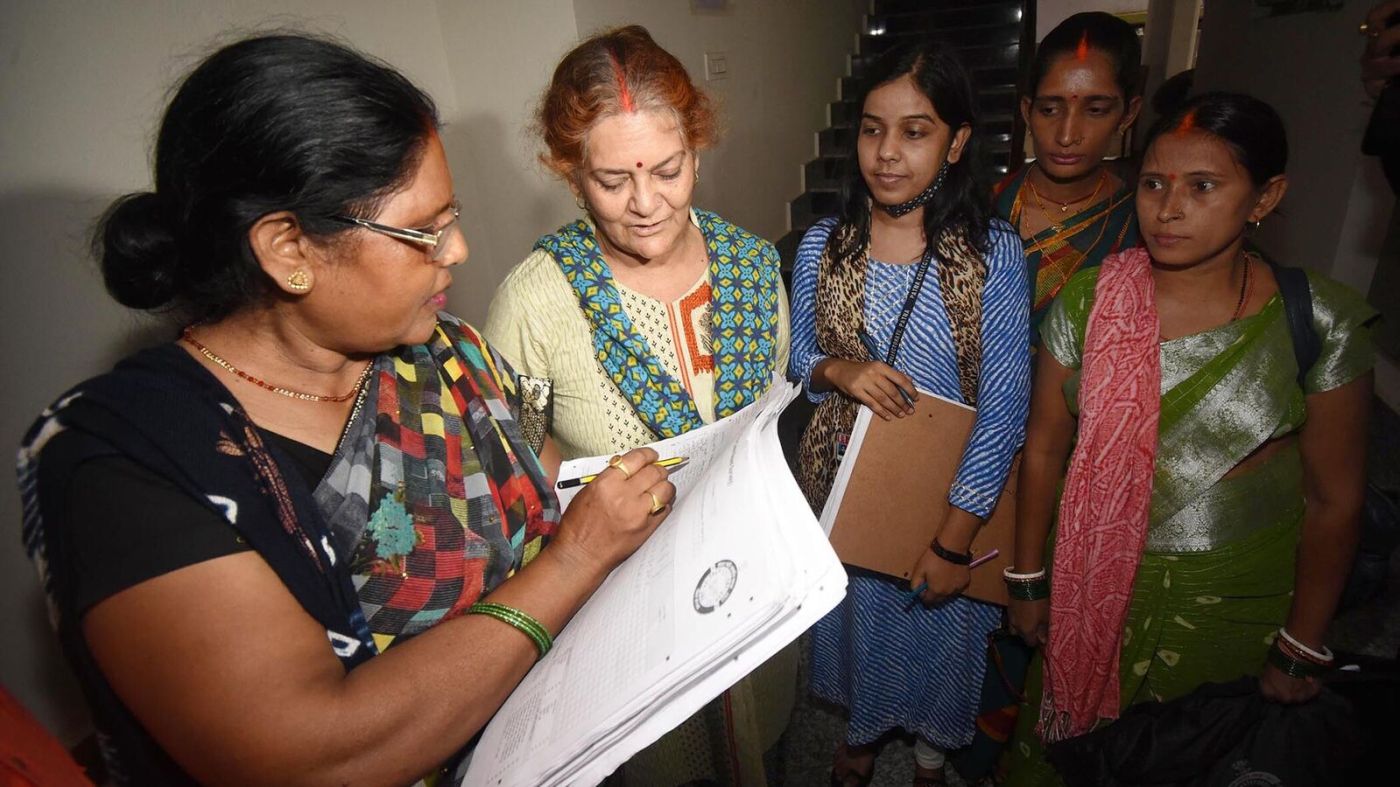

The Court in this case upheld the Bihar government’s competence to conduct caste-based surveys. These surveys involved enumerators and supervisors collecting caste information. The Court allowed the exercise on the grounds that, first, these surveys would assist the government to draft policies and make decisions for the society at large. The data could be used to quantify socially backward classes and enable their legal empowerment; second, the State Governments could not be expected to wait for the Central Government to undertake such regular surveys; and lastly, the survey, by collecting sensitive personal information did not breach the right of privacy.

Through this blog-post, I argue that the Court’s assessment regarding Bihar’s legislative competence is both erroneous and unconstitutional. I contend that first, the Court incorrectly examines Entries 69 and 94 of List I. These entries provide the Union Government with the power to regulate ‘census’ and ‘inquiries, surveys and statistics’ respectively. I seek to showcase that the Court heavily relies on reading in fundamental right evaluation while assessing legislative competence—an interpretation which could lead to disastrous consequences. Additionally, I argue that the Court’s reasoning on the meaning of the term ‘census’ is misplaced. Such an interpretation violates binding precedents on the interpretation of List I and the Seventh Schedule.

Fundamental Rights and the Seventh Schedule: A Collective Reading?

The petitioners argued that the State of Bihar did not have the competence to conduct a census. List I of the Seventh Schedule ,i.e., the list which mentions the activities which can be regulated solely by the Union contains two distinct entries— 69 and 94. Entry 69 mentions ‘census’ whereas Entry 94 states ‘Inquiries, surveys and statistics for the purpose of any of the matters in this List’. The argument is straightforward—the Union Government is the sole authority that can conduct a census or undertake inquiries, surveys and statistics. In response, the State argued that the fundamental right to equality mandates affirmative action, which cannot be effective unless data related to backwardness is collected. The Court agreed with the State and observed that:

“We cannot but; after the aforesaid discussions, at this point, emphatically say that the survey which is now initiated by the Government is within its competence since any affirmative action under Article 16 or beneficial legislation or scheme under Article 15 can be designed and implemented only after collection of the relevant data regarding the social, economic and educational situation in which the various groups or communities in the State live in and exist.”

The Court highlighted the positive duty on the State to ensure affirmative action and discussed a catena of judgments which made it mandatory that affirmative action is backed by reliable data. The Court stated that Article 246 (the origin of the division of powers under the Seventh Schedule) ‘had to be read’ with Articles 15 & 16. I argue that the combined reading of the legislative competence of governments along with fundamental rights is flawed.

First, such a position is not backed by the constitutional text. Article 246(1) is a non-obstante clause and provides the Parliament with the ‘exclusive’ power to make laws with respect to any matters in List I. Second, the Court failed to provide any support for this argument either from case law or other interpretative doctrines. The leading case on legislative competence and repugnancy is ITC Ltd. v. Agricultural Produce Market Committee which held that words in an entry cannot be given a narrow construction and have to be given the widest amplitude. The case does not mention the reading-in of fundamental rights as one of the tests while interpreting the Seventh Schedule.

Lastly, the use of fundamental rights while interpreting legislative competence could open a pandora’s box. If the Courts start to read rights and competence together, it could lead to arbitrariness and chaos. The judicial interpretation of fundamental rights has led the rights to be framed both widely and vaguely. The Court could use these vaguely-worded rights to override express divisions of power. For instance, suppose a State makes a law dealing with inter-state migration. Entry 81 of List I exclusively allows the Parliament to make laws relating to inter-state migration. If the Patna HC’s reasoning is taken a logical step ahead, it could mean that the State law could be upheld since the quashing of this law would affect the fundamental right to move freely throughout the territory of India (Article 19(1)(d)). All cases dealing with express provisions of the Seventh Schedule in the future would be subjected to the vagaries of judicial interpretation of fundamental rights.

Additionally, the Court’s reliance on the Directive Principles of State Policy and List III is highly misplaced. The Court stated that Entry 20 of List III refers to economic and social planning and Entry 23 deals with social security and social insurance; along with employment and unemployment. Thus, the conduct of a caste census is important to enable the States to pass laws on these subjects. The Court ignored the scheme of division of powers mentioned under Article 254(1) which provides primacy to the Union government in case of regulating List III matters. Moreover, these observations were secondary since List I clearly entrusts the regulation of census, inquiries, and surveys with the Union government. Furthermore, the Court stated that Article 38 and 39 provided the State with an obligation to secure a social order and promotes equality within the society. Per Article 36 read with Article 12, ‘State’ within this context means both the Union Government and the State Government. The interpretation of state to mean solely the State Government and the usage of directive principles to decide legislative competence warrants critique.

Meaning of the term ‘census’: Incorrect, Flawed and Misplaced

The State argued that the term ‘census’ in Entry 69 has not been defined anywhere—either in the Constitution or in the Census Act, 1948. The question thus stands: could Entry 69 prohibit any kind of survey which was in the nature of collecting data and enumerating data? In answering this question, the Court defined the terms census and surveys. The former meaning the connotation of accurate facts and verifiable details while the latter bringing forth only abstract opinions and perceptions of the subjects of the survey. Here, the State government was attempting to collect broad estimates and hence, this exercise was a survey. The Court further highlighted how the Census Act, 1948 allows for the involvement of state authorities as well. Lastly, the Court examined the Union legislation, Collection of Statistics Act, 2008 wherein ‘census’ and ‘survey’ has been used interchangeably. In the 2008 Act, State and Union governments both have been given this power to conduct surveys and censuses. This indicated that the Union allowed the States to conduct a census defined as per Entry 69.

Against this backdrop, I argue that the Court has misunderstood and misinterpreted the meaning of the term ‘census’ under Entry 69. First, it is erroneous to differentiate between the terms based on accuracy. In the case of Census Commissioner v. R Krishnamurthy, the Supreme Court had observed that census processes might be interfered with only if the policy framed is absolutely capricious, uninformed by reasons or is arbitrary. Hence, even incorrect estimates could be arrived at through the census which would be beyond judicial review. Second, such a distinction is unnecessary since Entry 94 includes ‘surveys’ as well. Third, it was shown by the petitioners that the nomenclature of the survey was artificial. An exercise similar to what the Bihar government wants to do was undertaken since 1951, most recently, in 2011 by the Union Government. Hence, it cannot be argued that this exercise was merely a survey and outside the purview of the Centre. Fourth, in the ITC case, it was held that an entry must be given the widest interpretation ever. If Entry 69 was given a wider meaning, it could include surveys and enumerations similar to the one attempted by the Bihar government.

Lastly, the Collection of Statistics Act, 2008 is incorrectly relied upon to buttress a questionable constitutional interpretation. The Court itself acknowledges that the terms ‘census’ and ‘surveys’ are interchangeably used which indicates that the drafter assumed that these terms mean similar things. A survey therefore could mean a census. Moreover, the mere fact that the 2008 Act allows the State to participate in certain statistical surveys does not indicate that it delegates the power under Entry 69 of List I to the State. I argue that this was a leap of logical reasoning since the 2008 Act could not be used to allow the State to undertake a caste census. In arguendo, I contend that the power to legislate still remains with the Union and only the authority to implement could be delegated to the State. Hence, the interpretation of Entry 69 to allow the State to conduct a caste census is flawed.

In this blog-post, I have sought to critique the several interpretations employed by the Court to allow the State of Bihar to conduct a caste census. I do not aim to evaluate the normative question: should States be allowed to conduct a caste census? The Census has been delayed by six years making it extremely difficult for policies to effectively cover the exact number of beneficiaries. Moreover, the term ‘census’ continues to remain undefined. This could mean that if the tests employed under the ITC case is used, even the basic attempt at collecting data could possibly be included within the umbrella term. Bhatia in his new book, the Indian Constitution: A Conversation with Power argues that a wide approach of interpretation re List I, ‘entrenches the centralizing approach within the field of legislative relations’ (Page 18) and privileges the Union Law. Additionally, such an interpretation might be best-placed in a unitary constitution and not a federal constitution like ours whih leads to skewing the power in favour of the Union in case of a conflict (Page 18).

Against this backdrop, it would be fitting for future benches to strike a correct balance by efficiently reasoning the meaning of the term ‘census’ in a (supposedly) federal constitution. Would the Courts do it, and how, is a completely different story waiting to take place.

The Author is a Research Fellow at the Charkha, Centre for Constitutional Law (Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy)

Image Credit: Press Trust of India

Leave a comment